An article in the Times yesterday about the Puget Sound’s job recovery following the dot-com bust got me thinking again about the oft-claimed jobs to home prices correlation. The usual assertion goes something like this: “Prices are justified because our economy is strong (i.e. – lots of jobs), and as long as we keep adding more jobs, home prices will not stop increasing, because more jobs equals more demand.” It’s certainly a comforting belief for inflated housing enthusiasts to hold when the local job situation is on an upswing:

Even though it ended on a somewhat muted note, 2006 was still the best year for job creation in Washington in nearly a decade, according to figures released Tuesday by the state Employment Security Department.

The state averaged nearly 2.87 million nonfarm payroll jobs last year, a gain of 3.2 percent, or 91,500 jobs, over 2005’s average. That was the most nonfarm jobs added in a year since 1997, when 98,600 were created.

The year-end figures also show that 2006 conclusively marked the Puget Sound region’s full recovery, in terms of total jobs, from the dot-com collapse and subsequent recession of the early 2000s.

The article included a nice graph showing the number of jobs in the four-county region since 2000. It has been well demonstrated in other markets that job growth or loss does not directly relate to home prices, but I thought it would be interesting to compare the Seattle Times graph with some data from the Seattle Bubble spreadsheet to see how well the more jobs = more demand = rising prices claim has held up in King County over the last five or six years. To obtain data about the number of jobs in King County I went to Workforce Explorer, the source cited in the Times article.

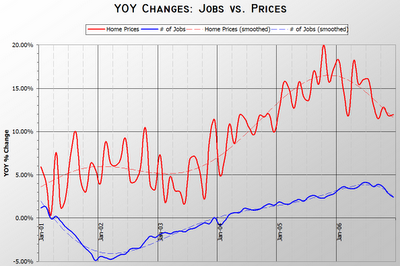

First I present you with the graph that comes closest to supporting the view that jobs are the primary source of demand.

When you compare the percent change year-over-year in both the number of jobs and the median (residential only) home price, the curves actually almost line up, with both job and home price changes being increasingly positive from about early 2003 to the end of 2005. However, the total change in home price increases during that time went from +7.3% to +20.0%, while the total change in jobs went from -1.9% to +2.3%. Despite the similar curves, I think it would be difficult to argue that such a slight change in the job situation drove the major price increases seen over the same period.

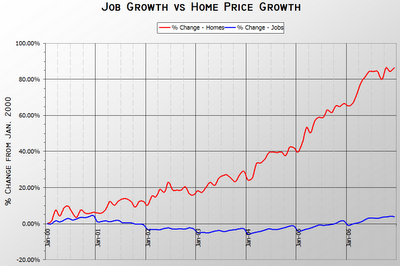

Here is same data presented in a slightly different way:

At the end of 2006 there were roughly 4% more jobs in King County than January 2000, yet home prices had increased a whopping 85%. I’d like to hear the logic that tries to argue that such a paltry increase in jobs will cause that large of a price increase in homes.

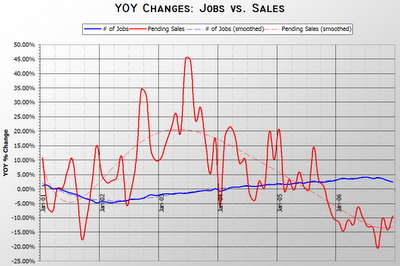

Now let’s take a look at home sales. Supposedly the improving job situation is driving demand, and demand is measured by sales, so let’s see how the two compare.

Hmm. It would appear that sales were experiencing the strongest growth during a time when the number of jobs was actually declining. In the summer of 2003 sales were up by as much as 45% over 2002, and yet the job market was still declining by roughly 1.5%.

Looking at the raw numbers of jobs versus sales the disparity becomes even more clear:

If jobs are supposed to drive demand, why is it that once the number of jobs began to increase in early 2004, sales actually leveled off? And why have sales been dropping off so steeply in the last year despite what the Times reports as “the best year for job creation in Washington in nearly a decade”? Could it be, perhaps, that the number of home sales and prices of sold homes in fact have very little to do with the number of jobs in a region?

I challenge anyone out there that still believes more jobs = more demand = rising prices to show me the data that supports any sort of correlation between those data sets. Lacking that, I hope we can finally put this dead argument to rest.

All of the above graphs—and the data behind them—can be downloaded in Excel format.

(Drew DeSilver, Seattle Times, 01.17.2007)

(Workforce Explorer, Industry Employment: Historical Series, 01.2007)