Since property tax season has rolled around here in the Seattle area again, I thought it might be a good time to demystify one aspect of property taxes that has often confused home owners during this housing bust.

If you’re like many local home owners, the county’s assessment of your home has probably dropped around twenty percent over the last few years, but your property tax bill has continued to rise.

So what gives? If the value of your home is falling, how can your property taxes still be going up?

One factor that might cause your property tax bill to go up regardless of the value of your house is that Seattle area voters are prone to constantly passing new levees for things like schools, libraries, and low income housing. These are usually voter-approved measures that tack on an extra few cents per thousand dollars of assessed value, and adding a handful of these to your bill could easily offset whatever decrease may have seen in your assessment.

However, even without additional property tax levees, it is likely that your taxes may still be increasing, despite having a home that is worth less every year. The easiest way to understand how this is possible is to consider a simplified scenario.

Let’s say you live in the imaginary Emerald County, which contains only two houses. You and your neighbors—Hunter and Addison Taite—have identical homes that were built at the same time on the same size lot, with all the exact same upgrades.

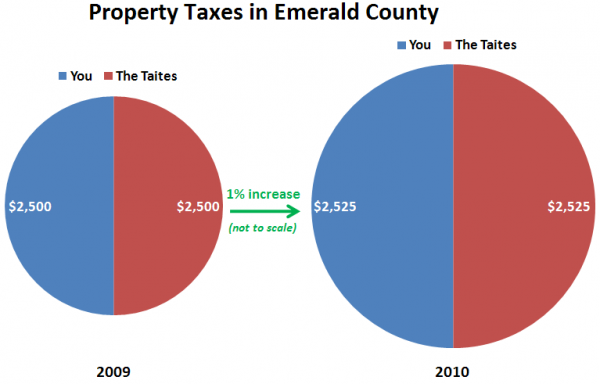

In 2009, Emerald County collected $5,000 in property taxes. Since both your homes were assessed at the exact same value of $500,000, that bill was split right down the middle between you and the Taites, $2,500 each.

Now you and the Taites have just gotten your bill for 2010’s taxes, and you both find that although Emerald County’s assessed value of your home has dropped to $480,000, your bill has gone up to $2,525.

This is because your home’s assessment does not directly determine the amount of taxes you pay. Instead, it only determines how much of the county’s total property tax collection you are responsible for. Additionally, Washington State law allows municipalities to increase their total property tax collection by a maximum of one percent each year.

In the example above, your share of Emerald County’s total tax collection in 2009 was 50%, so you paid 50% of $5,000. In 2010, Emerald County boosted their total property collected by the maximum amount allowed by the state, upping it 1% to $5,050. Since both your house and the Taites house fell in value, you each still owe 50% of that total, so you each saw a 1% increase in your bill.

Obviously the reality of counties with hundreds of thousands of homes is much more complicated, but hopefully this gives you the basic picture. The take-home point to remember here is that your home’s assessment determines your share of the total tax bill, which is essentially guaranteed to rise about one percent per year.

Therefore, if all the homes in your county (or city, or school district, etc.) are falling in value at roughly the same rate, then your tax bill will continue to go up. If your home is falling in value faster than most in the county, your tax bill might go down, but if it is falling in value slower than most other homes, you might see an increase of even more than one percent.

Stay tuned later this week for an additional look at property taxes, including a closer look at assessments. Next time I promise to bring more statistics, charts, and graphs.